My House Among the Dead

- Bill Shaw and R. Lee Kellems

In December 1997 I moved into the house where I now live. The white house on 5875 N. Keystone (Rural) which is owned by my Uncle Ray and Aunt Reba. When I've told people where I live I've always said "you know that house by the tombstones on the corner of Keystone (Rural) and Kessler." Every since I've moved in I've been wondering about those tombstones next door and about my "dead neighbors". When I asked my Aunt Reba she said that she thought they were just historical markers of some sort.

Back in February a friend of mine, Biruta Grisulitus, who also lives in the neighborhood said "you know this whole neighborhood was a cemetery don't you? They just built the neighborhood right on top of it." I have to admit that part of me was skeptical. After all I thought that they can't just build right on top of a cemetery. It's got to be illegal after and who would want to do such a thing even if it wasn't illegal?

Still partially doubting (but not completely) Biruta's story about the neighborhood I asked a co-worker and friend, Nancy Dynes, about it. Nancy lived in the neighborhood for several years so I figured that she might know something about the neighborhood and the cemetery. Nancy said "Oh, yeah. It's all true it was a cemetery."

I didn't find out anything more about this story until July 1998 when Nancy asked me "Did you read about your (dead) neighbors in the paper?" I hadn't but Nancy pointed out that the Indianapolis Star printed the story that is "reprinted" below.

Read this story and you will learn about the people buried there (including Revolutionary War Veterans), how history was lost and partially recovered from man's "progress", about a woman who publishes books with blank pages, corporate apathy, and the mission by a self- described "nobody" to preserve part of the past before it is too late.

| - R. Lee Kellems |

NOTES:

As I find out more about this and get my own photo's developed I will update this page. By the way in phone # you can see the roof of my house in the upper left hand corner.

Last Rights - by Bill Shaw, writer for the Indianapolis Star & News A historic cemetery in the heart of Indianapolis was all but destroyed when a "nobody" came to the rescue.

(reprinted from the July 13, 1998 edition of the Indianapolis Star and News)

Ever wonder why there is a cemetery or monument or whatever it is at the southeast corner of Keystone Avenue and Kessler Boulevard, one of the busiest intersections in Indianapolis?

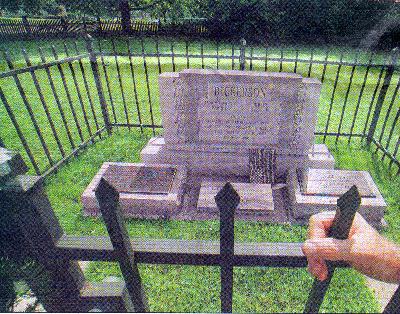

It's a neatly groomed quarter-acre lot with an old maple and buckeye surrounded by a wooden picket fence and presided over by the flags of the United States and Indiana. Beneath the flags and inside a black iron fence are three stone markers.

MEMORIAL: The markers at the corner of Kessler and Keystone are the result of Kokomo resident Dorothea Sargen'ts personal quest to honor war veterans and early Indiana settlers.

Since you can't read the markers from the street and there's no place to park, the curious often pull into Mildred Crash's wine-and-beer-making shop across the street. Mildred doesn't mind, but she has no answers.

"I don't know a thing about it, and I've been here 27 years," exclaimed the 78-year-old proprietor (with her son Ivan) of the Wine-Art Indianapolis shop at 5890 N. Keystone Ave.

White-haired Mildred wears a T-shirt proclaiming: "This Beer is Damn Good." She promptly launches into an enthusiastic lecture on the virtues of wine-and-beer-making.

What about the cemetery?

"Is that what it is? People stop in here all the time about it, and I say "I've been here 27 years and don't know a thing about it. ' I didn't know it was a cemetery. I thought it was decoration."

After 27 years, Mildred Crash would like some answers. Jesse Pool is 78, a retired elementary school principal. He and his wife, Mary Lois, bough their house on Kessler in 1953 when it was a quiet, two-lane street arched over with towering maple trees.

DISCOVERY: Jesse Poole (left) and Lee Ellis, who live a couple of blocks down Kessler, say that they've only recently learned about the Keystone and Kessler cemetary's history.

Pheasants flew low through their yard, and riders on horses walked along a bridal path by the peaceful street. Glendale Center was still a cornfield, and nearby Keystone Avenue ended at 72'st Street on the south bank of the White River. Today 110,000 cars a day cross the congested intersection where pheasants flew and horses strolled.

Jesse is a Republican precinct committeeman and vice president of the neighborhood association. A bird poops in the neighborhood, and Jesse knows about it.

"I know nothing about that cemetery, though. It's kind of a mystery. How did it get to be a cemetery?" he wondered. "When we moved here, it was a vacant lot with broken bottles."

The answers to Jesse and Mildred's questions are found in a most peculiar place, far from the curious corner with the fluttering flags.

NORTH TO THE ANSWERS

Dorothea Woods Sargent lives in a 10-foot-wide mobile home beside busy U.S. 31 in Kokomo behind a 36-foot-long truck trailer full of junk encircled by an 8-foot-tall cyclone fence and eight barking dogs.

An enormous portrait of President Dwight Eisenhower hangs on one wall, two plastic fly-swatters on another and books on genealogy fill every flat surface in the impossibly cramped trailer.

Five read leather bound books by author Dorothea Sargent, including Dorothea's Reader and The Sargeants of Mud Creek rest on the bookshelf. The pages of the book are blank. No words.

Why do you self-publish books with no words, Dorothea?

"I always wanted to write books," she explained. "I just didn't have all the words."

Anyway, Dorothea is 81 and was married to John Sargent, a prominent Northeastside businessman and descendant of a Hoosier pioneer family named Dickerson. Dorothea was married to John 18 or 20 years, she's not exactly sure. He died in 1991 at the age of 98. That, she's sure about. It was a complex relationship.

While she was living on Sargent Road with John Sargent, he told her about his ancestor's graveyard at Kessler and Keystone. It was a weedy vacant lot, and this offended Dorothea. The dead should be honored, she believed, setting forth on a mission to correct an injustice.

THE DEAD AND THE DAR

Dorothea's story unfold in colorful fashion, drifting from Pocahontas and Norman Rockwell to her mother's royal ancestry and back to John Sargent and the old forgotten cemetery.

Somehow, somewhere, some way, driven by mysterious internal forces, Dorothea raised $3,400 in 1984 from fellow members of the Daughters of the American Revolution and erected the imposing stone work and flag poles in the cemetery.

"God directed me," explained Dorothea with a shrug. No big thing.

Indiana law required abandoned cemeteries to be cared for by the township trustee's office, Obviously, over the long years various Washington Township trustees ignored the old cemetery and allowed it to disintegrate.

When Dorothea began bombarding the Washington Township trustee with passionate letters and long, rambling phone calls, the lot was cleaned, grass cut and a wooden fence built around her memorial.

The current Washington Township trustee, Gwendolyn M. Horth, conceded that Dorothea's private quest to preserve the corner saved it from further ruination.

"It was a vacant long 14 years ago, and now it's not," the trustee said. "Mrs. Sargent deserves the credit."

RECORDS SPARSE

Briefly, in 1835, Hiram and Mary Bacon deeded the land to "the citizens of Washington Twp. And their heirs forever" as long as a "burying ground." Exactly how much land they deeded is now impossible to determine.

Hezekiah Smith, a Revolutionary War veteran, was the first to be buried in what became known as Bacon Cemetery. When Crown Hill Cemetery opened in 1864, several bodies were moved there. How many and who they were is unclear.

In the early 20'th century, more and more graves were moved to Crown Hill, more records were lost, and a "developer" named George Kessler built a street east of Keystone, named it after himself and destroyed a portion of the cemetery.

Today, the official record of Bacon Cemetery in the Washington Township trustee's office consists almost entirely of Dorothea's rambling letters. No burial records. No Names. Nothing, although hundreds of people were buried in the area. By the time the trustee's office took over the cemetery, everything had been lost, tombstones knocked over and dead people paved over.

The Dawson and Culbertson cemeteries, also located east of what is now Keystone Avenue, have been completely obliterated and no longer exist, bulldozed beneath tons of concrete and asphalt.

Vernon Earle, 73, a retired engineer, remembers finding his great-great- grandfather's 1862 gravestone in the old Dawson cemetery at Rural Street and Kessler when he was a kid. One day in the early 1950's, he returned to find his great-great-grandpa's gravestone gone. It, along with others, had been dumped in a landfill by a "developer," A house now sits on his great-great-grandfather's grave.

In 1994, the City-County Council allowed Methodist Hospital to build a clinic at the northwest corner of Kessler and Rural, despite ferocious opposition from Jesse Poole, his outraged neighbors and a heartsick Vernon Earle.

"We fought a corporation and lost, of course," said Jesse.

How many graves lie beneath the clinic is not known. A human femur bone was churned up by an auger during construction. Oh well, probably just somebody's mom or dad.

"It's a horrible, sickening desecration that went on in that whole area," said Vernon Earle, "How'd you like your ancestors underneath a house or an office building or road?"

PAVING THE PAST

The civic-minded Bacons of 1835 envisioned a burying ground forever commemorating the lives of early settlers who hacked a village from the thick Indiana wilderness. Instead, when no one was left to complain, bodies were paved over, official records of their lives lost, or their tombstones tossed in landfills.

Many of those graves contained veterans of the American Revolution, men who fought to create the United Sates of America. Oh well.

Were it not for the passion of an old woman who lives in a Kokomo mobile home and self-publishes books with no words, the last quarter-acre of the Bacon burying ground would probably be a fast-food joint, muffler shop or tanning spa.

The stone marker Dorothea Sargent established commemorates Revolutionary War veteran Robert Dickerson, his family and distant descendants, including her late husband, World War I veteran John Jacob Sargent, The Dickerson family is believed buried beneath the marker.

"Organized and Designed by Dorothea Wood Sargent 1984" says the marker beneath the flags and the Dickerson stone.

Dorothea is now saving portions of her monthly Social Security checks to buy a sign that says "Hiram and Mary Alice Bacon Cemetery" so the 110,000 daily motorists will know what it is.

"I'm 81, and my days are numbered, but I'll get it done," she says, "The Lord has spoken."

Mildred Crash of Wine-Art Indianapolis was surprised to hear about Dorothea Wood Sargent's quiet obsession to honor nameless people who lived over 160 years ago and got paved over and every last trace of their existence erased from earth.

"You don't say - Revolutionary War people, and the whole intersection was probably a cemetery," said Mildred Crash, "I thought it was just decoration. Now I can tell people it's about Revolutionary War people."

Meanwhile across the street, Jesse Poole, guardian of the Brockton neighborhood, had noticed a broken board in the cemetery fence along the street where pheasants once flew low and Hiram and Mary Bacon envisioned a proper burial ground forever. Jesse went home, got a hammer and fixed it.

"We owe a great deal to this Mrs. Sargent, whoever she is," Jesse said.

No one in this neighborhood has ever met Dorothea Wood Sargent.

"I'm just a nobody," she said.